It has been discussed by many that our brains are wired on an evolutionary scale, and that the rapid change of society through technological advances has outpaced us, leaving us with many disconnects between what we see every day and what we can actually handle. In many ways, we might be happier if we lived in small tribes and were closely surrounded by wilderness, instead of surrounded by brick and cement, drive vehicles and get visual stimuli from computer or television screens. One aspect of this disconnect, that I find quite intriguing, and I think is central to our ability to understand the world we find ourselves in, is what I call and order of magnitude problem.

Think about early man in those hunter gatherer days. Counting is a base cognitive skill, important for our survival. But what is that we might count? You might count the amount of fruit gathered on any particular day, the number of children, or people. Such numbers might get you into the 100s. You might count seasonal cycles. If you were lucky maybe you had 80 of those to count. You might count lunar cycles. Getting you to about 1040. Even this would require some note making, because this is counting over time, and surely you would not sit there and count something that high. Such cycles of time were the only things worth keeping track of. We had no need to measure time beyond that. No need for small units of time such as a second. It might make sense to come up with some unit of measurement for distance. Something comparable to arm lengths or hand widths…something we might use to size an animal, measure height of people or spears. When it came to traveling, you might then simply use something like phases of the moon, or number of diurnal cycles. Once again such counting would leave numbers small. Occasionally you might find yourself thinking about numbers in terms of fractions. Maybe something like half a day, or a quarter of an armlength. For things very small, you probably would no longer use armlength as your standard, but perhaps finger width. Such techniques are ones that we still use today.

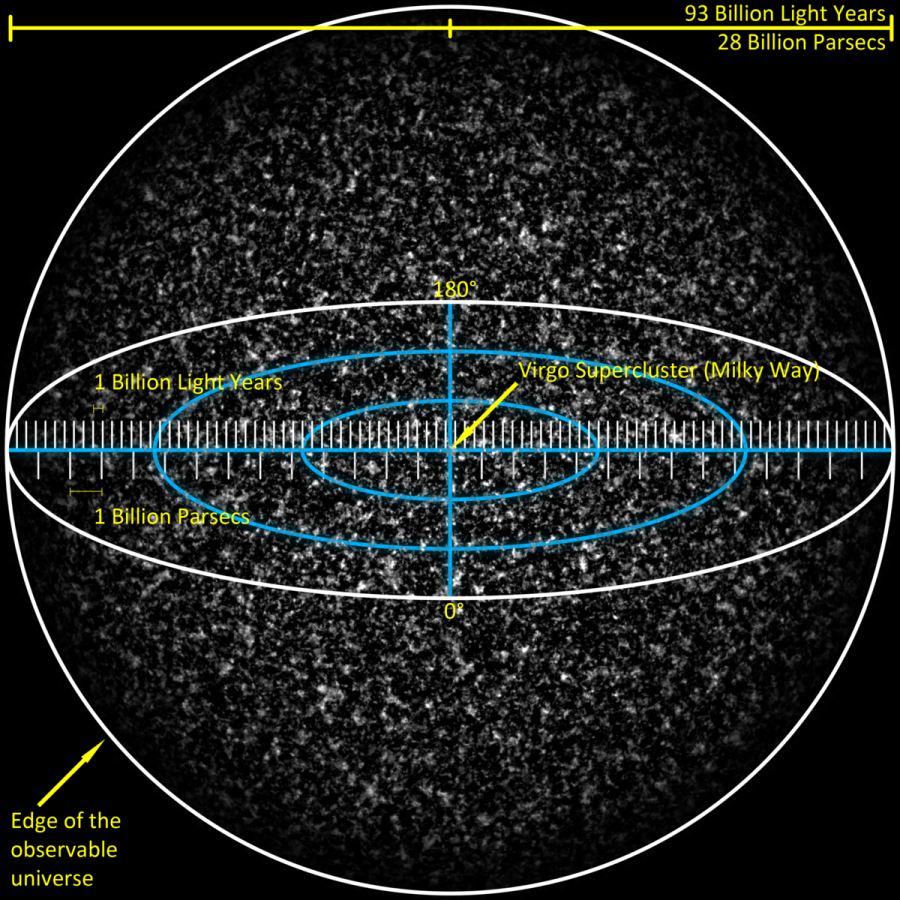

The reality is that if you think about numbers, you probably won’t get very far. Now do a little exercise for me. If you think of the number 1000. How do you think about it, to picture a 1000 of something? You might think what a $1000 can buy, but money is a fiction that represents a quantity of stuff you can buy which varies depending on what stuff your buying. If you wanted to actually count, what would you think about. Maybe 1000 people in a room. You might have a sense for how big a group that is. Chances are you won’t get it exactly. Go down to a 100 and your chances of picturing 100 things gets better. Now do 10 of something. Pretty easy. Now do 1. Even easier. Let’s go down another order of magnitude. Try to think of something that is 0.1. Here as we move down an order of magnitude we can no longer count whole things. So think of 1/10th of a person probably gets a bit graphic, so what are you thinking of to imagine 0.1? For that you now have to think of some standard. Maybe a mile, an inch, a meter? Depending on what you choose, you can do okay. Now try 1/100th. Again with the right starting point you might do okay, but even dividing by 100 can be hard for someone without a formal education and once we get to 1/1000th our ability to guess at the meaning of that fraction is severely reduced regardless of our starting point. So if you are keeping track this puts the human mind, on a good day our brains are capable of somewhat accurately sorting out 5 orders of magnitude (10-2 – 103). However, if we look at the scale of the universe in size we span 52 orders of magnitude from the plank length to the size of the observable universe (please see this very cool interactive graphic that allows you to explore the different spatial scales of the universe). In terms of time, our quantum clocks can measure up to 1 ten billionth of a second (10-10) . Meanwhile we know the universe has been around for about 14 billion years (1015 seconds). If you don’t have trouble digesting such numbers you are a super genius, because everybody should. Those are just the extremes, but unless you are within that 5 orders of magnitude range I discussed earlier, it makes little difference. And this is also important because it means that a million miles, might as well be a billion miles in our head. However, the difference between those two numbers is meaningful. In science, to consider two numbers like that the same would be to make a grievous error on the order of 100,000%.

Scientists, through years of working with the numbers that shape our world are often better at dealing with these things, but even scientists tend to use conventions to make numbers easier to manage. There is a reason why you don’t measure the distance from New York City to Boston in inches. We have developed different units of measurement for distance. In the old English system we have inches, feet, yards and miles. In metric, we have prefixes that span numerous orders of magnitude so that we don’t have to always report distance in meters. For objects in space in our solar system we might use astronomical units to keep those distances in more manageable numbers. For things outside our solar system, light years.

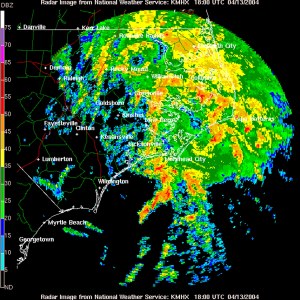

Whatever we measure in science can change over large ranges and change at massively different rates. Change is rarely linear, but very often exponential. As a result, we might find ourselves dealing with quantities which very over several orders of magnitude. In my field a good example for this is radar reflectivity. You may not be familiar with it, but you’ve certainly seen radar images if you’ve paid attention to the weather. Higher reflectivities indicate bigger drops and faster rain rates. Lower reflectivities represent light rain or drizzle. The difference in size between a drizzle drop and a basic rain drops is no more than a factor of 10, but the reflectivities span over 10- 1,000,000. Thus, meteorologists convert those reflectivity values using decibels. The decibel system was initially used for sound given the large range of frequency for sound waves, but now is a common tool for expressing values that vary over several orders of magnitude by taking the logarithm (base 10) of the value. This reduces the number to its order of magnitude. For example, instead of 106 if I take the logarithm with base 10 of that number I get 6. And 6 is much easier to wrap our heads around than 1,000,000. I know I’ve gotten kind of technical here with this example, but the point is that nature, as we’re discovering, does not conform to the numbers our brains had to deal with when we evolved. And most scientists, while they might have some understanding of the microscopic or macroscopic numbers and the wide ranges of values science employs, to objectively analyze and come to some meaningful conclusions we very often have to be able to visually see those numbers between about 0.01 and 1000.

You might say that such numbers make little difference to most of us unless we are in science, but let’s talk about where our everyday lives might be impacted. First let’s start with the population of the world. There are 7 billion people. Try to wrap your head around that number. Is your soul mate really just one in a billion? Could such a large group of people create an environmental disaster? How many bodies could certain countries throw at you in a war? About 700 million, globally, live in abject poverty. Do the numbers seem so voluminous that it’s easier to ignore human suffering, or make you feel defeated before you try?

What about some of the more important educational and scientific controversies that still exist today? Evolution has been happening for several billion years, but many would like to believe that we’ve been around for only 6000 years. Religious dogma aside, isn’t it possible that part of the reason that some people resist what science clearly demonstrates is because we are talking about a length of time that few can relate to? The vastness of time threatens to humble us all as blips in a universe far older than we can fathom. And its size and origin similarly attacks our human conceit at being the grandest and cleverest design in a creator’s eye.

Vast amounts of people also create vast sums of money. Billionaires have almost unimaginable wealth that people still commonly believe that can obtain too. Politicians and media constantly throw large dollar values in our faces to intimidate us. When one wants to high light wasteful spending we can put point to something costing 100’s of millions of dollars and we shudder at such an amount being wasted. Forgetting that with 100 million taxpayers, something in the 100’s of millions is costing us a handful of dollars a year. I have seen the tactic used frequently. Once again we might on some level realizes that a 100 million, 10 billion, and a trillion dollars are different, but they are all unimaginably large sums of money that in the battle for what’s important and what’s not, they can all be seen as being on equal footing. The idea that public television and radio need to be cut for austerity is quite simply a joke when compared to a 10% increase in defense spending if anybody thinks that’s going to balance the budget.

One might argue that the microscopic matters very little (no pun intended), but I do think an appreciation for that scale is valuable, if for no other reason helping us appreciation the vast variation of scales that make up our known universe. Scientists often take very small numbers that might exist for pollutants or toxicity in foods or water, and change the unites of those numbers so that they are bigger. I understand why, because of course we don’t want to underwhelm in those situations, but maybe it’s also a problem that we continue to cater to this limited range of numbers that our minds most easily manage. It’s probably best to start incrementally, and perhaps a good example of how we can begin is with time. John Zande over at his blog, The Superstitious Naked Ape, offers up a good first step towards our lack of comfortability with numbers outside of our “sweet spot”. The start of our counting of years begins with the birth of Christ, but this is a religious and faith based reason to start the counting of the years. Why not use Thai’s bone which is our earliest evidence of careful astronomical observations of the sun and moon over a 3 ½ year period. Instead of the year 2017, it would instead be 15,017.

It might seem like an arbitrary difference, but I think it would give us a better feel for the vastness of time, and a better appreciation for the numbers that shape the universe we’ve come to know. Since there seems to be little stopping the advance of science in technology, perhaps we better find more ways to help these brains, made for a different time, catch up.

Superb post, Swarn. As I was reading, I was reminded of this quote:

LikeLiked by 7 people

Thanks Victoria, that is the perfect quote to go with this post! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the way using the thais bone flips our entire perspective of humanity. It’s not a perfect starting point, but it’s a fund mind game.

Awesome post. This should be a lecture.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you John. And yes I agree that adding of about 10,000 years is really important from a cognitive point of view in thinking about ourselves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah but 15017 would be more trouble to write on a check. (yes I am inherently that lazy)

Intriguing post Swarn. It is interesting that our calander is based on a fictional tale perceived to be true by diehard fanatics unwilling to accept the factual evidence of an old earth.

I have played around with billions a bit in my observations of Uranus and Neptune. Just that boggles my head in a unique fashion. Being able to see planets in our solar system (relatively, and repectively) 1.5 billion and 3 billion miles away kind of blows my mind. Of course I have also seen galaxies in the Virgo cluster much much further away, but the planets just have a way of driving the point home as to how far is a billion?

At least we don’t generally have to say “in the year of our lord” every time we cite a calander date anymore.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well you wouldn’t be that lazy if you been doing it all your life! lol

Yeah…maybe my post should have been titled, touching the infinite…but I did want to try to at least address the microscopic too. I think though that it takes some time dealing with these numbers to really contemplate them and become comfortable with them. You astronomy hobby is a great way to do that. Few people have such hobbies that help them experience numbers on that scale.

LikeLike

Given the influence that Christianity has had in shaping western culture, marking our calendars from the birth of Christ has more significance than merely religious. Nevertheless, if it was decided that a change in calendars was in order, clearly we should just switch to using stardates. I mean, we’ll have to change anyway once we develop the warp drive. Might as well get ahead of the curve. As you may know, following the French Revolution, the French introduced a new calendar (along with clocks and the metric system). The calendar and clocks (there were more than one) didn’t last more than a few years, but we still have the metric system, so that’s something.

Perhaps more useful to your discussion, one of the pieces of equipment that I use at work is an RF amplifier which we use to drive an acousto-optic modulator. We use the modulator to turn off a laser beam, which it can physically achieve in about 0.2 us, but only if the amplifier is sufficiently fast, so when I speak to vendors, I tell them I need an amplifier that can turn off in less than 20 ps. Every once in a while, I’ll stop and think about what I am asking, be slightly in awe about both the reality and absurdity of the situation, and then usually ask if then can do it in 10 ps.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I meant nanoseconds, not picoseconds. I think I just proved your point. We have no concept of time or space outside of a few orders of magnitude.

LikeLiked by 2 people

And I didn’t catch the mistake either, which proves my point as well. Although I did think there had to be some sort of mistake because the time you gave in ps was basically the highest resolution of time we have with the atomic clock and any device you might be building with an atomic clock would be a very expensive one. lol Billions, millions…I’m not sure. lol

LikeLiked by 1 person

It might have shaped western culture, but as I’m sure you’ll admit we have an entire globe of culture, and even western culture has connections to older civilizations. The west did not develop in a bubble free from influences from China, India, Egypt, Babylon, and Sumeria. So it’s certainly a calendar bias, which may have been excusable at the time, but certainly not now, given what we know of the flow of science and technology in world history.

And yeah the French tried to change the way we measure time as well, but I suspect that the main problem there was that clock making was still relatively hard back then, and to change the way clocks were made would have been an extraordinary nuisance, and more importantly it would have required the changing of every map. Since it is the hexigesimal system that Babylonians used for making maps that continued to be used throughout history (this is where minutes and seconds come from). Map making is still difficult, but computers do it all rather well and could transform the gridding on maps rather easily. Back then it would all have to be redrawn by hand. I don’t know if the French had volunteered their services in that regard. lol

LikeLike

I fully agree. In the context of globalisation, there’s a strong case to be made that basing the year on the birth of Jesus (who ironically was born approximately 3 B.C. if I remember correctly) is not culturally relevant. I only took issue with your claim that it was merely religious. Between 900-1500 which is when I think A.D./B.C. came into common use, it was highly culturally significant, much more than basing the year on the reign of a Roman emperor.

LikeLike

Smashing post, Swarn

Basing our dating system on the extremely dubious birth of a narrative construct tacitly gives the nod to Christianity whether we like it or not. And the god botherers do like to remind everyone of this on a semi-regular basis

If we are going to base our time on … our time, then why not push it back as far as the estimate the Human Genome Project has us… say, for argument’s sake, 100,000 years?

That would pretty much kill off the Ken Ham Club, and show the Lake Tiberius Pedestrian Fan Club how inconsequential their little make beleive man-god really is.:)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Ark. I agree, that it would be great to push it back even further. I wouldn’t even complain if we literally started it back to the age of the Earth. Why just celebrate human trips around the sun? The fact that the earth has done it 4.5 billion times is truly remarkable. The vastness of time I think is important to a meaningful conception of the universe. Even a 100,000 years is small potatoes…but as I said to JZ, even adding 10,000 years would be an important cognitive step!

LikeLike

How would we write the date , I wonder?

Or maybe …

As an example.

Approximately 2.5 billion BTR ( Before T. Rex), around tea time.

And to express the date post /em> cataclysm that wiped out the dinosaurs:

”It was a rainy Wednesday afternoon,in November, 65 mill WTF….”

LikeLiked by 1 person

LOL Yeah I mean I think it might be natural for us to take such a large number and think…the 4 billion doesn’t matter all that much between one year and the next, so let’s just lop it off. I have thought about this problem a bit. One possibility is to somehow incorporate the logarithm a bit into the date. So for instance you could say the date is 2017.9.63. The inverse log base 10 of 9.63 is about 4.5billion, but that of course leaves us with the fact that this number isn’t going to change appreciably from year to year so we’d likely just lop it off. And this doesn’t really solve the problem of putting the vastness of time into our consciousness either other than the through education, which is arguably what we could be doing anyway…although in my experience with students a better understanding of logarithms would help!

With things only changing one year at a time, it does seem inevitable that we might simplify things. What’s interesting is that when I grew up in the late 1900s (obiously) people would commonly refer to dates by just the last two numbers of the year. The fact that we’ve entered a new millennium seems to have prevented people from saying…oh yeah I remember that song came out in ’05. I don’t know…but I suspect that as we get deep enough with this century it might happen. Perhaps a breakthrough in our lifespan might change that habit a bit.

Any type of post script is also likely to fall away. Nobody really uses A.D. either. The Thai bone solution, therefore, almost seems best…just adding an extra digit isn’t too intrusive, even though it still leaves us woefully short of the mark in terms of understanding times depth. Maybe some mathematician might have some clever ideas on this front.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t look at me. Maths was never my strongest subject at school. I thought vulgar fractions were ones you were allowed to swear at. And I did … a lot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“In many ways, we might be happier if we lived in small tribes and were closely surrounded by wilderness, instead of surrounded by brick and cement, drive vehicles and get visual stimuli from computer or television screens. ” Such an excellent observation and one I concur with heartily.

What an insightful post altogether. The importance of numbers cannot be diminished by ignoring the potential truth they contain. Being born with a strong sixth sense or two, I’ve actually had a singular opportunity to ‘see how the universe is wired,’ though those are only words and that’s how I would describe it. Something like the Matrix and not. I immediately thought of Einstein. Because what I ‘saw’ were numbers. The universe I witnessed was wired in numbers beyond imagining. I wondered why I wasn’t trained as a mathematician, then let it all go.

Another point. When you asked what 1000 conjured, the first thought that popped into my head was, ‘not much.’ Everything in our lives is over the top compared to even 10 years ago. 7 billion people – which I consider often when traveling and seeing all the food people stuff in their faces and the rubbish piling up. Thinking where do they all live, how much do they consume, how do they dispose of, and of course this is a road that leads down the path of how many more years this can continue, then the numbers begin shrinking down, down.

Great stuff, thanks for the read.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Bela for your kind words. Perhaps I didn’t ask the question properly, but I was trying to get at asking, how you would picture 1000 things. Could you accurately conceive of a 1000 people, or a 1000 skittles…because in many ways 1000 of something is probably similar to 2000 of something in our conception. This is very different than when we think of 100 and most certainly 10. The point is that we go up order of magnitudes our brains ability to fathom such numbers diminish to a point in which everything just becomes ridiculously large and inconceivable. And it is not surprise that we would think that given how we’ve evolved.

And yes you are quite correct…I see numbers similarly myself in the world around us, equations too now that I’ve taken enough physics. lol Makes it a much more fascinating and wondrous place.

LikeLiked by 2 people

No, you asked the question properly. My answer was based on ‘first take,’ rather than ‘answering the question put.’ Just how the Gemini mind works 😉

LikeLiked by 2 people

“So think of 1/10th of a person probably gets a bit graphic, so what are you thinking of to imagine 0.1? For that you now have to think of some standard. Maybe a mile, an inch, a meter?”

Depends how generous you’re feeling I’d have thought.

Hahahahaha.

Such an absorbing post Swarn, one of the most interesting I’ve read for a while.

– Esme counting flying monkeys upon the Cloud

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you Esme. LOL I appreciate your kind words. It might sound extremely nerdy but I do spend time trying to contemplate the macroscopic and microscopic. I feel it’s important, and I wanted to try writing about this topic to demonstrate how our relationship with numbers is disconnected to our understanding of the universe. It’s an interest problem.

LikeLiked by 1 person