Recently a ridiculous graphic was going around showing how somebody could live on $2000 dollars a month, still save $100 a month and have a couple hundred dollars spending money too. Of course that person didn’t have children, most of the costs seemed to be typical of the 90s, and in order to clear $2000 dollars a month you still need to be making $13 or $14/hr which is nearly double the federal minimum wage. For those of you who don’t want to do the math, by saving $100, they could potentially get a year of college after 10 years of work. So, by 60 they could have their bachelor’s degree and maybe move up in the world.

If that sounds ludicrous, congratulations, you are a sane person. But more importantly that $100 (we could even bump it up to $200) a month savings isn’t going to just sit they’re happily waiting to be spent on something big in most cases. A capitalist society has many rags to riches stories, and while such stories typically rise to the forefront of the conversation, they are a vast minority. Why? Because they depend on luck. I think a capitalist society can be set up in a way to give more opportunities to people, but that’s not through an unrestrained free market. It requires a government that is actively restraining it.

What I really want to talk more about are the ways in which the society we live in is stacked against poor people. I find the GOP talking point that poor people are lazy to be one of the most insidious ever devised and one that causes not only continued financial misery for poor people, but also dehumanizes them, diminishing their human dignity and value.

When I was 20 I worked a summer job where I sold Cutco knives. I’ve met other people who did the same thing; lured in by the promise of $11/hr for summer work, only two find that this was $11 for a 1 hour demonstration and you had to go into people’s homes and try to sell them knives. I’m not a great salesman, because I hate dictating how people should spend their money. Nevertheless they were quality knives and I did okay. I was reminiscing about the job recently because I actually bought some Cutco knives off of eBay as I accidentally melted one of the handles off a knife I kept from sample set that I earned by selling enough knives. Anyway, I remembered how they taught us to explain that cheap knives might work great at first, but they dull or break quickly. So without buying good knives, over the course of some number of years you would actually lose money. The company was trying to justify why you would spend a lot of money (they were quite expensive, average $70 a knife in the early 90s) on a set of knives. Let’s take for granted that these are quality knives and that you would save money in the long run. I was smart enough back then to know that this wasn’t how the real world worked for many people. Putting $800 down for a set of knives, no matter how great, was not the kind of capital people had lying around just for knives. Interestingly the thing that broke me was when the mechanically cheery regional sales manager told me to target middle class people because they were likely to have more money saved up than upper middle-class people who were more likely to have been frivolous with their money and might have less saved up. So I was expected to take savings away from people who I felt could put their money to better use buying their kids new bikes for what amounted to only kitchen knives.

When I was 20 I worked a summer job where I sold Cutco knives. I’ve met other people who did the same thing; lured in by the promise of $11/hr for summer work, only two find that this was $11 for a 1 hour demonstration and you had to go into people’s homes and try to sell them knives. I’m not a great salesman, because I hate dictating how people should spend their money. Nevertheless they were quality knives and I did okay. I was reminiscing about the job recently because I actually bought some Cutco knives off of eBay as I accidentally melted one of the handles off a knife I kept from sample set that I earned by selling enough knives. Anyway, I remembered how they taught us to explain that cheap knives might work great at first, but they dull or break quickly. So without buying good knives, over the course of some number of years you would actually lose money. The company was trying to justify why you would spend a lot of money (they were quite expensive, average $70 a knife in the early 90s) on a set of knives. Let’s take for granted that these are quality knives and that you would save money in the long run. I was smart enough back then to know that this wasn’t how the real world worked for many people. Putting $800 down for a set of knives, no matter how great, was not the kind of capital people had lying around just for knives. Interestingly the thing that broke me was when the mechanically cheery regional sales manager told me to target middle class people because they were likely to have more money saved up than upper middle-class people who were more likely to have been frivolous with their money and might have less saved up. So I was expected to take savings away from people who I felt could put their money to better use buying their kids new bikes for what amounted to only kitchen knives.

The knife example is like many things in our society: good quality things that last longer are the better option to buy if you want to save money in the long term. However, to get those savings you need to have money to begin with. I remember when I was a grad student, and had limited income when I was buying a blender; there were many cheap choices that seemed like a good deal. And they would often work great for a little while, but invariably break down after a year or two. Capitalism has done a great job of making these things at a cheaper and cheaper cost, but the trade off is durability. It’s a piece of equipment that works for a limited amount of time,because they know poor people have limited amounts of money and on any given month they can only afford a cheap blender; and in a year they will be able to afford another cheap blender.

There are many more examples like this. You can reduce energy costs in your home by getting solar paneling on your roof, but it is an expensive investment and the energy savings might only make up for the cost after 10 years. You can afford to do this only if you have a nice house and the capital to invest in the first place. Another caveat is that even if poor people did want to invest in a house, it is likely not one that is well built enough to invest in something like solar paneling.

Let’s go back to that budget I talked about at the beginning where somebody with $2000 a month is able to put away $100-200 a month in savings. People who are poor generally have:

- Cheaper/older appliances

- Cheaper/older car

- Older and cheaper living accommodations

- Cheaper or no health care, thus high co-pays and deductibles

All it takes is a broken water heater, fridge, or washing machine, a car breakdown or accident, or a medical emergency for all those savings to be wiped away. And these problems will occur more frequently as a result of what you can afford when you’re poor.

Let’s throw in some other important factors. In our society, nutritious food costs more and thus families with lower quality foods may suffer more health consequences adding to their medical costs. As the COVID situation is showing us, poor people don’t get to social distance and stay home from work easily. To survive they depend on their social network and this can lead to worse outcomes in terms of getting sick and missing more work and school. The way public school funding seems to work here is that property taxes are a large part of the funding. Poorer communities get less equipped schools, can’t afford to pay their teachers as much and thus have less teacher retention, with the most experienced teachers unlikely to stay.

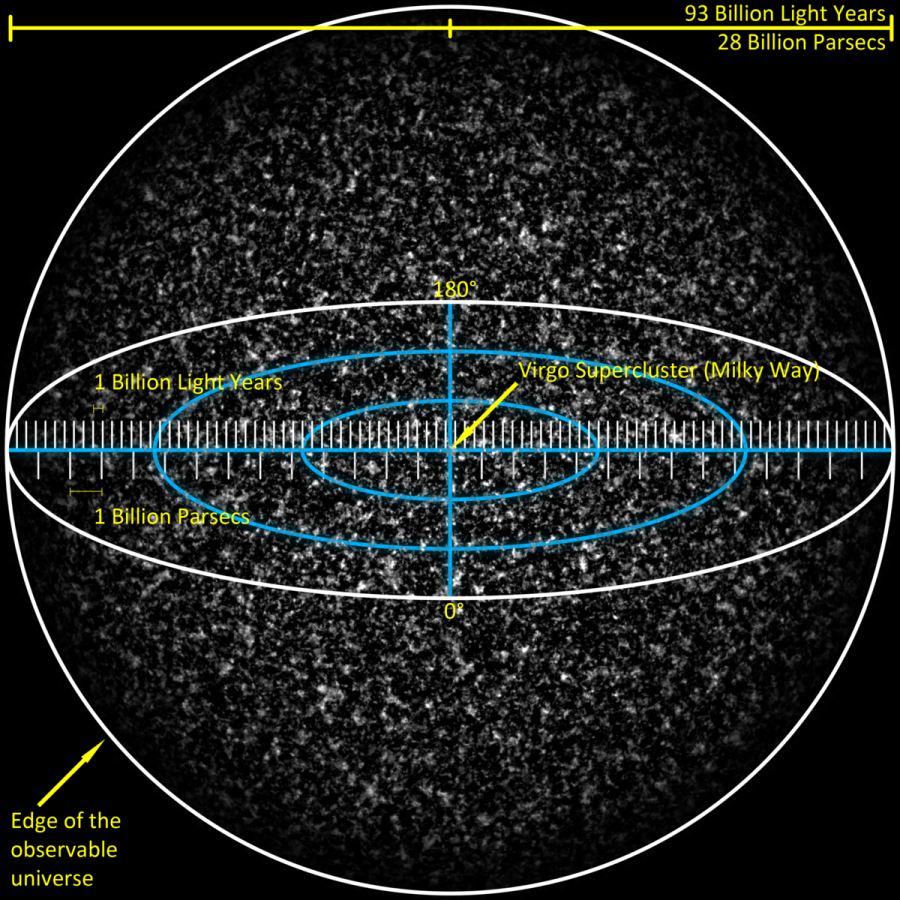

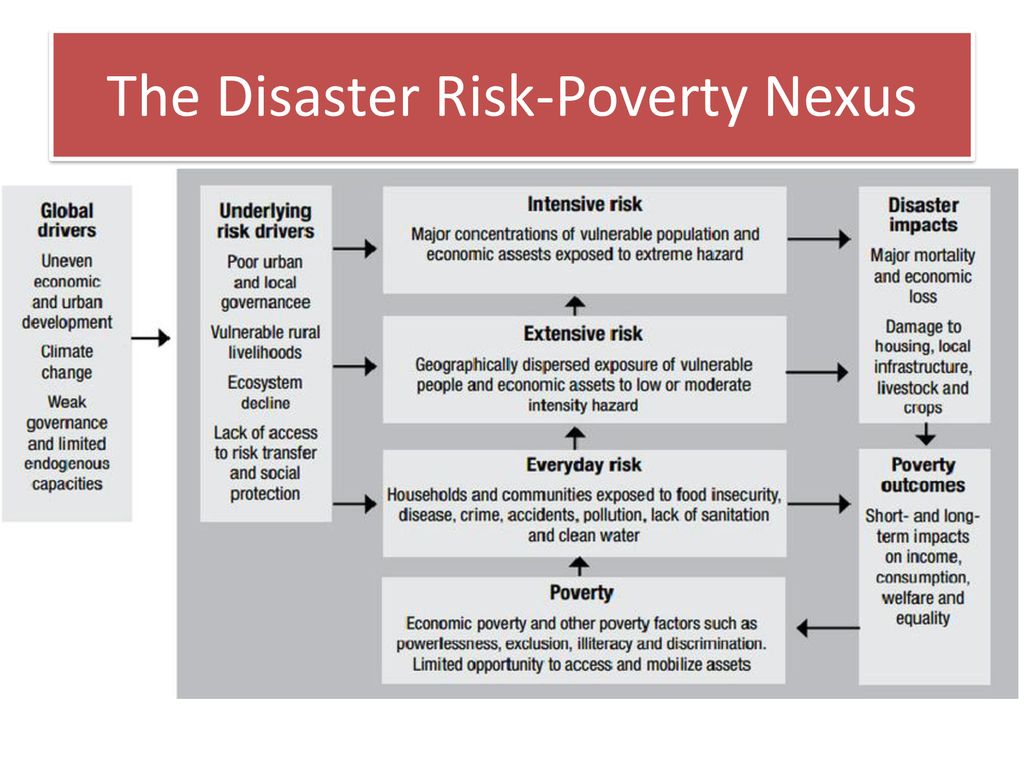

Another thing people might not be aware of is that poorer communities also tend to be in more disaster prone areas. Consider living near a river. There are places that are less likely to flood and more likely to flood. But instead of just not letting people live in flood prone areas, developers build cheap housing there for people with less money. It’s relatively inexpensive to rebuild if the area gets wiped out and this keeps insurance costs down in riskier areas. Meanwhile, a poor home owner in a flood zone is less likely to be able to afford and purchase flood insurance. So as poor person you are also just more likely to have your life wiped out by a natural disaster. There are also many other factors that increases disaster risks for people in with lower socioeconomic standing.

It’s possible that a parent taught you a lot about cars and you know how to fix them yourself and spot a good used car. But that’s not everybody. It’s possible that you are great at sniffing out good deals for quality appliances, but that takes time: a luxury money also gets you. Getting a higher education can also be a great way to get you out of poverty. However, this is becoming increasingly unaffordable without taking on significant debt, which in turn keeps you in a state of perpetual struggle for at least a decade after you graduate. So maybe you get lucky and stay healthy, have few car issues, end up in a good school district, or are gifted genetically in some way that gives you an advantage. And of course there could be any number of issues that your parents have which might limit your ability to rise very much in life. A lot of people may be working hard, but only some will be able to rise out of poverty.

Capitalism doesn’t care if you put away money as long as you are buying something. In fact, it prefers you spend your money rather than save it. It makes much more money off people buying multiple cheap blenders than a good quality blender that lasts 10 years. In fact, it is in capitalism’s best interest to not make things last for anybody. It seems that as the middle class erodes we just have rich people who can buy new expensive items every couple years; not because they have to, but because they can change their aesthetic anytime they want. Meanwhile poor people are forced to repeatedly buy cheap goods they have to replace often just to have a functioning home or vehicle. Capitalism is also in general happier if you are sick more and need to buy pharmaceuticals instead of being able to have the leisure time to keep healthy, exercise, and buy nutritious foods.

The real insult is that this capitalist engine, working exactly as intended, accuses the very people it exploits of being lazy and stupid, performing worthless jobs that they should be thankful for because it is only by the grace of their corporate overlords that they haven’t already been replaced by machines. When workers start to demand enough money to get by on they get replaced by machines anyway because heaven forbid some CEO can’t afford to replace his 7th vehicle that year that’s parked unused at their 4th mansion most of the year. If you listen to conservatives a CEO is the hero in this story: he is better, smarter, and a harder worker, deserving of his riches, and possessing of a superior morality. Should they screw up on that front, however, that’s okay. They have friends in the corporate media, they can hire the best lawyers and pr firms, and escape with barely a dent in their fortune. And sure some small percentage fall from grace, and while many people will recognize such people as criminals, others will simply say “Well if he’s really guilty, he surely would be in jail”. Trump is a good example of how rich criminals support each other. Meanwhile poor people pay for even the most minor of crimes for a lifetime. Capitalism not only exploits poor people as workers, but also exploits them as consumers, all the while devaluing their very existence.

This system’s cracks are showing. It can’t sustain itself. Creating division among the population is its last-ditch effort to keep itself alive. And so far, it’s working. How much longer can it all go on?